THE BATTLE OF SHERIFFMUIR 1715 |

|

In 1707 the two kingdoms of Scotland and England had been united, a highly unpopular move across much of Scottish society. The Jacobites sought to exploit this not simply to reverse the union, but to gain the crown of both England and Scotland. An abortive rising took place in 1708. Then, in 1714, when the Elector of Hanover succeeded Queen Anne to the throne he alienated a range of former supporters of Anne. One of these, the Earl of Mar, threw in his lot with the Jacobites and in September began to raise forces to march south to join with English Jacobites, in an attempt to return a Stuart to the throne. |

|

|

The Jacobite forces deployed with boggy ground on their left flank; though Reid suggests this was unintentional and caused further disruption to the Jacobite deployment. However, it may be that they intentionally exploited this ground, unsuitable for cavalry action, to anchor their flank and enable the massing of their inexperienced cavalry on the right flank, giving them at least some advantage in numbers against their far more experienced adversaries. Both armies outflanked each other on their right wings, frequently intentionally the stronger of the two cavalry wings in historic battles. The Jacobite attacks were somewhat disordered, but on the right they were successful and drove off the Hanoverian left who had still not fully deployed and seem to have been caught in the flank by the Highlanders’ charge. These Jacobite forces of the right then continued in pursuit of the routed forces, thus losing the opportunity to attack the exposed flank of the remaining forces of the government centre. On the Jacobite left the Lowland forces also attacked but were met by well deployed government troops, who held the Jacobite attack. The frozen marsh seems to have enabled government foot though not cavalry to manoeuvre on the Jacobite left flank. The Jacobites were driven back in a fighting retreat as far as the River Allen east of Kinbuck, during which many were probably killed, particularly at the crossing of the Allen. |

|

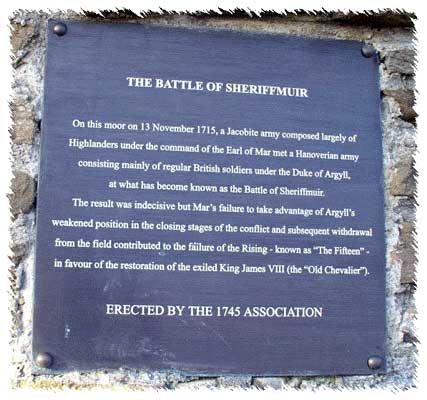

The returning troops from the Jacobite right seem to have stood on Kippendaive Hill but were not brought back into the action. Argyle, with perhaps 1000 troops of his right wing, comprising men returning from the pursuit towards the Allen, drew up in enclosures and mud walls for protection. Thus the original location of the action was largely abandoned and the forces in the final phase may have approached from almost opposite directions to where they originally deployed. The final Jacobite advance faltered within musket range and they withdrew as dusk approached. Though neither side could claim a genuine victory, the momentum of the rebellion had been broken and it soon then petered out An obelisk monument to the Clan Macrae, erected 1915, stands on the battlefield. The Gathering Stone is a block of grit, since 1840 enclosed in an iron cage, where the standard of the Scottish clans is said to have been placed. It is in reality a much earlier standing stone but one which has gained traditional association with the battle. |

|

|

© Paisley Tartan Army 2008-09