WILLIAM WALLACE Circa 1270 - 1305 |

|

William Wallace is one of Scotland's greatest national heroes, undisputed leader of the Scottish resistance forces during the first years of the long and ultimately successful struggle to free Scotland from English rule at the end of the 13th Century. Records of Wallace's life are patchy and often inaccurate. This is partly because early accounts of his heroic deeds are speculative, and partly because he inspired such fear in the minds of English writers at the time, that they demonised him, his achievements, and his motives. Many of the stories surrounding Wallace have been traced to a late-15th Century romance "The Wallace", ascribed to Henry the minstrel, or "Blind Harry". This epic is vehemently anti-English in language and tone. The most popular tales about Wallace are not supported by documentary evidence, but they show his firm hold on the imagination of his people. He represented the spirit of the common man striving for freedom against oppression, and exposed the Scottish nobility of the time as a group of unprincipled opportunists. |

Wallace was translated from the archaic latin. On his seal it says he is the son of 'Alan'.] His mother is believed to have been the daughter of Sir Hugh Crawford, Sheriff of Ayr, and he is thought to have had an elder brother, also called Malcolm. Because he was the second son, William did not inherit his father's title or lands. At the time of Wallace's birth, Alexander III had already been on Scotland's throne for over twenty years. His reign had seen a period of peace, economic stability, and prosperity and he had successfully fended off continuing English claims to suzerainty. King Edward I (known as Edward "Longshanks") came to the throne of England in 1272, two years after Wallace was born. |

|

In 1286, by the time he was about sixteen, Wallace may have been preparing to pursue a life in the church. In that year, Alexander III died after riding off a cliff during a wild storm. None of Alexander III's children survived him. After his death, his young granddaughter, Margaret, the 'Maid of Norway', was declared Queen of Scotland by the Scottish lords, but was still only a little girl of 4 who was living in Norway. An interim Scottish government run by 'guardians' was set up to govern until Margaret was old enough to take up the throne. However, Edward I of England took advantage of the uncertainty and potential instability over the Scottish succession. He agreed with the guardians that Margaret should marry his son and heir Edward of Caernarvon (afterwards Edward II of England), on the understanding that Scotland would be preserved as a separate nation. Margaret fell ill and died unexpectedly in 1290 at the age of 8 in the Orkney Islands on her way from Norway to England. 13 claimants to the Scottish throne came forward, most of whom were from the Scottish nobility. In this climate of lawlessness, William Wallace's father was killed in a skirmish with English troops in 1291. It is likely that the death of his father at the hands of the English contributed to Wallace's lifelong desire to fight for his nation's independence. However, little is known about Wallace's life during this period, except that he lived the life of an outlaw, moving constantly to avoid the English, and occasionally confronting them with characteristic ferocity. Carrick's describes Wallace's skills as a warrior: "All powerful as a swordsman and unrivalled as an archer, his blows were fatal and his shafts unerring: as an equestrian, he was a model of dexterity and grace; while the hardships he experienced in his youth made him view with indifference the severest privations incident to a military life." |

Balliol took an oath of fealty, paid homage to Edward, and was accepted in Scotland. However, Edward I's motives had not really been to help the Scots as an arbitrator. He saw himself as the feudal superior of the Scottish crown, and wished to install a Scottish monarch whom he could manipulate. |

|

|

Edward underestimated the Scots' belief in their own sovereignty. When he sought to exert his suzerainty by taking law cases on appeal from Scottish courts to his own court in England, and by summoning Balliol to do military service for him against France, he turned the Scottish throne against him. In the meantime, England had been at war with France. In 1295, a treaty was negotiated between Edward I and the French that provided for the marriage of John de Balliol's son Edward to the French King's niece. Edward demanded the surrender of three castles on the Scottish border and, on John's refusal, summoned him to his court. John did not obey, and war was inevitable. Edward marched north with his armies. After a five-month campaign, he conquered Scotland in 1297. Following his victory, he appointed his own agents to enforce peace in Scotland. He deposed and imprisoned John de Balliol and declared himself ruler of Scotland. He also had the Stone of Destiny, the coronation stone of Scone, taken south to Westminster. The government of Scotland was placed in the hands of Englishmen led by Hugh Cressingham, the Earl of Surrey. Outside the south-east corner of Scotland, there was widespread disorder, and defiance against the English was increasing. Wallace was involved in a fight with local soldiers in the village of Ayr. After killing several of them, he was overpowered and thrown into a dungeon where he was slowly starved. Wallace was left for dead, but sympathetic villagers nursed him back to health. When he had regained his strength, Wallace recruited several local rebels and began his systematic and merciless assault on the hated English and their Scottish sympathisers. As his support grew, Wallace's attacks broadened. In May 1297, with as many as 30 men, he avenged his father's death by ambushing and killing the knight responsible and some of his soldiers. Now, he was no longer merely an outlaw but a local military leader who had struck down one of Edward's knights and some of his soldiers. William Wallace had become the king's enemy. Although most of Scotland was in Scottish hands by August 1297, Wallace successfully recruited a band of commoners and small landowners to attack the remaining English garrisons between the Rivers Forth and Tay. Wallace and his co-leader, Sir Andrew de Moray, marched their forces towards Stirling Castle, a stronghold of vital strategic importance to the English. The English commanders must have been falsely confident that the upstart Scots would retreat or surrender. On Sept 11, 1297, the English army under John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, confronted him near Stirling. Wallace's forces were greatly outnumbered, but Surrey had to cross a narrow bridge over the River Forth before he could reach the Scottish positions. Wallace's men lured the English into making an impulsive advance, and slaughtered them as they crossed the river. English fatalities are reported to have approached 5,000, gaining Wallace an overwhelming victory. He had shown not only that he was a charismatic leader and warrior, but also that his tactical military ability was strong. Never before had a Scottish army so triumphed over an English aggressor. Wallace captured Stirling Castle and for the moment Scotland was almost free of occupying forces. |

|

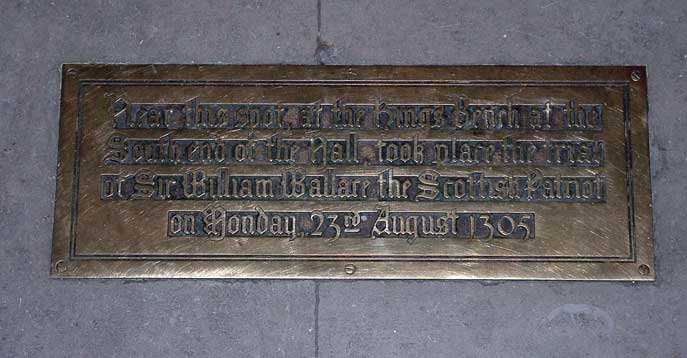

At the time of the battle of Stirling Bridge, Wallace and de Moray were both in their late twenties. Neither could yet claim to be Scottish national heroes, and they were not recognised by their aristocratic enemies in Scotland as anything more than local commanders. Under Wallace, the Scots, - commoners and knights, rather than nobles, - were united in a focused fight for freedom from foreign rule. Whereas the Scottish nobility had usually given in to English demands for allegiance, Wallace's patriotic force remained unequivocally dedicated to the struggle for Scottish independence. In October of 1296, Wallace invaded northern England and ravaged the counties of Northumberland and Cumberland. Upon returning to Scotland early in December 1297, he was knighted and proclaimed guardian of the kingdom, ruling in Balliol's name. In less than six years, he had risen from obscurity to become Sir William Wallace, holder of one of the most powerful posts in the kingdom. Nevertheless, many Scottish nobles lent him only grudging support, and he had yet to meet Edward I in a head-on confrontation. From the autumn of 1299 until 1303, nothing certain is known about Wallace's activities. There is some evidence to suggest that he went to France with several loyal supporters on a diplomatic mission to seek support from King Philip IV. Philip may have furnished him with letters of recommendation to Pope Boniface VIII and King Hakon of Norway. Then, in 1303, the Treaty of Paris effectively ended hostilities between England and France. Having made peace with the French, Edward renewed his conquest of Scotland in earnest. He captured Stirling in 1304, and although most of the Scottish nobles pledged allegiance to the English crown, he continued to pursue the outlaw Wallace relentlessly. Edward's refusal to acknowledge Wallace as a worthy enemy from a separate country meant that the English could officially regard Wallace as a traitor to the English nation. On Aug 5 1305, Wallace was betrayed by a Scottish knight in service to the English king, and arrested near Glasgow. He was taken to London and denied the status of a captured soldier. He was tried for the wartime murder of civilians (he allegedly spared "neither age nor sex, monk nor nun"). He was condemned as a traitor to the king even though, as he correctly maintained, he had never sworn allegiance to Edward. |

|

|

On 23rd August 1305, he was executed. At that time (and for the next 550 years), the punishment for the crime of treason was that the convicted traitor was dragged to the place of execution, hanged by the neck (but not until he was dead), and disembowelled (or drawn) while still alive. His entrails were burned before his eyes, he was decapitated and his body was divided into four parts (or quartered). Accordingly, this was Wallace's fate. His head was impaled on a spike and displayed at London Bridge, his right arm on the bridge at Newcastle-upon-Tyne, his left arm at Berwick, his right leg at Perth, and the left leg at Aberdeen. Edward may have believed that with Wallace's capture and execution, he had at last broken the spirit of the Scots. He was wrong. By executing Wallace so barbarically, Edward had martyred a popular Scots military leader and fired the Scottish people's determination to be free. Almost immediately, Robert I the Bruce revived the national rebellion that was to win independence for Scotland. He succeeded and was crowned king of Scotland in 1306. On his way to reconquer Scotland, Edward died near Carlisle. Several hundred years later in the 19th century, statues commemorating Sir William Wallace were erected overlooking the River Tweed and in Lanark. In 1869, the 220-foot high National Wallace Monument was completed on a hill near Stirling. This huge tower now dominates the area where the Scots fought their most decisive battles against the English in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries at Stirling Bridge and Bannockburn. Following the re-discovery of William Wallace's seal in 1999, the Ayrshire case has began to gather momentum. The seal identifies Wallace as the son of Alan Wallace and not Malcolm and Alan Wallace appears in the Ragman Roll of 1296 as a 'crown tenant in Ayrshire'. Dr. Fiona Watson in 'A Report into Sir William Wallace's connections with Ayrshire' (March 1999), carries out a detailed reassessment of William Wallace's early years and concludes 'Sir William Wallace was a younger son of Alan Wallace, a crown tenant in Ayrshire'. On reading this report the renowned Wallace historian, Andrew Fisher, concedes 'If the Alan of the Ragman Roll was indeed the patriot's father, then the current argument in favour of an Ayrshire rather than a Renfrewshire origin for Wallace can be settled' |

The Sons Of Scotland would like to thank ELECTRIC SCOTLAND for all they're help with this history lesson |

BRAVEHEART KILLING TOPPED THE BILL AT FAIR!! |

|

|

William Wallace's execution was the opening attraction of a giant medieval carnival, according to research which sheds new light on the freedom fighter's death in August 1305. The killing of 'Braveheart' Wallace, during which he was hanged, drawn and quartered, is now believed to have marked the opening of Bartholomew Fair - the largest medieval market in England, held annually for centuries to commemorate St Bartholomew's Day on August 24. Tens of thousands flocked to Smithfield - the site of his execution - for the fortnight-long celebration, which featured vast cloth and meat markets as well as sideshows, musicians, wire-walkers, acrobats, puppets, freaks and wild animals. The fair, which was first held in 1133, was unique in that everyone from peasants to the upper echelons of England's aristocracy attended. By the 18th century it was one of the most spectacular national and international events of the year. It ended in 1855. The convener of the Society of William Wallace, David Ross, who discovered the link, said: "Wallace was captured near Glasgow on August 3, 1305, and was rushed to London, where he arrived on August 22nd. "I had always wondered why he was taken down to London in only 19 days, which included some time during which he was kept at Dumbarton Castle, where his famous sword was left. "The English king, Edward Longshanks, had Wallace rushed to London, where his trial was hastily set up at Smithfield, facing St Bartholomew's Church. "Unlike most prisoners, who were thrown into dungeons to languish for months or even years, Wallace appeared in London on August 22, was tried on the 23rd and executed immediately after. That is extremely unusual, but until now we have never known why - other than that Wallace was to be made an example of. "But Bartholomew Fair presented the perfect opportunity for King Edward to demonstrate his power to the maximum number of people. "A vast number of people thronging to the medieval fair would have seen the champion of Scotland torn to pieces, and known what would happen to those who crossed Edward." Ross added: "Bartholomew Fair was the biggest fair in the country - the population of London doubled as traders came from far and wide to Smithfield. "The fair centred around St Bartholomew's feast day, and at its focal point was St Bartholomew's Church, outside which Wallace was executed. "It was customary for the Lord Mayor of London to open the fair formally at that place on St Bartholomew's Eve - the very day Wallace was executed. "It seems clear that Wallace's hideous murder was the fair's opening spectacle, timed perfectly for the day when most people congregated from all over the country - and led by the Lord Mayor himself to commence the celebrations." |

WALLACE'S EXECUTION |

|

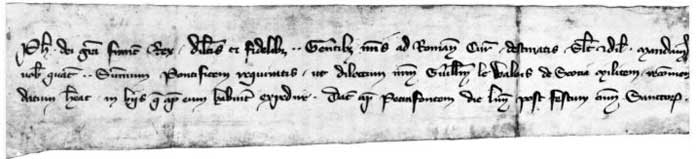

William Wallace’s early successes did not last. His co-commander Andrew Murray died, leaving Wallace alone as Guardian of the Kingdom to face a superior English force under Edward I himself at the battle of Falkirk in 1298. He lost. His credibility ruined,Wallace resigned the Guardianship, but did not give up the fight. He never surrendered to Edward and Edward always excepted him from any offers of clemency. Having served Scotland abroad by diplomacy in France,Wallace returned to Scotland. On 3 August 1305 he was betrayed to the English and captured. On 23 August he was executed. What follows comes from an 18th-century transcript of a medieval manuscript from the Sir Robert Cotton collection, which was lost in a fire in 1731. It is a contemporary record of Wallace’s ‘trial’ and sentence in London before an English court acting on behalf of a king whose authority Wallace never recognised. It is a translation from the original Latin. William Wallace, a Scot, and born in Scotland, a prisoner for sedition, homicides, plunderings, fire-raisings, and diverse other felonies came and, after the same justices had read out how the aforesaid lord the King had in hostile manner conquered the land of Scotland over John Balliol, the prelates, the earls, the barons and other enemies of his of the same land, in forfeiture of the same John, and by the conquest of him had submitted and subjugated all the Scots to right of ownership and his royal power as their King, he had received in public the homages and pledges of the prelates, the earls, the barons and very many others, and he had made his peace to be proclaimed throughout the whole of the land of Scotland. He had appointed and set up the Guardians of that land, appointing the sheriffs, the provosts, the bailies and other ministers of his, in his place, to maintain his peace and give justice to all whomsoever according to the laws and customs of that land. The aforesaid William Wallace, forgetful of his fealty and allegiance, raised up all he could by felony and premeditated sedition against the same lord the King, having united and joined to himself an immense number of felons, and he feloniously invaded, and attacked the Guardians and ministers of the same King, feloniously and against the same lord the King’s peace, insulted, wounded and killed William de Heselrigg, sheriff of Lanark, who [ ] the appointments of the said King in the regular meeting of the county court, and afterwards in contempt of the same King without reason fought against the same sheriff whom he had killed. Thenceforth with the entire multitude of those who adhered in arms to him and to his felony, he invaded the towns, the cities and the castles of that land, and had his letters [orders] sent throughout the whole of Scotland, as if they were the letters of the superior of that land. He held and appointed parliaments and conventions after all the Guardians and ministers of the aforesaid lord the King of the land of Scotland had been evicted by William himself, and unwilling to restrain himself to so much wickedness and sedition, decreed to all the prelates, earls and barons of his land who adhered to his party, that they were to subject themselves to the fealty and dominion of the King of France, and they were to press for help towards the destruction of the kingdom of England. Taking some also from his accomplices with him he invaded the kingdom of England, as in the counties of Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmorland, and all whom he found there who were in the fealty of the King of England, he feloniously put to death in various ways. |

|

He feloniously and seditiously slaughtered religious men and monks dedicated to God, and burnt and laid waste churches constructed for the honour of God and the saints, together with the bodies of the saints and other relics of them that had been honourably collected therein; he spared no-one who spoke the English language, but afflicted all, old men and youths, wives and widows, children and babes in arms with a more grievous death than could be considered. And so, every day and every hour, he seditiously and feloniously persisted in contriving the death of the same lord the King, and the destruction and the manifest weakening of the crown and his royal majesty. And it is clear that after such outrageous and horrible deeds, the aforesaid lord the King, together with his great army, had invaded the land of Scotland and had defeated the aforesaid William, who was bearing his standard against him in mortal warfare, and other enemies of his, and had granted his true peace to all from that land and had mercifully taken the aforesaid William Wallace back into his peace, the said William seditiously and feloniously, whole-heartedly and undauntedly persevering in his above noted wickedness, disdained to submit himself to the aforesaid lord King’s peace and to come forth to it, and so was publicly outlawed in the court of the same lord the King as traitor, robber and felon, according to the laws and customs of England and Scotland. It is clearly both unjust and in disagreement with English laws and it is held true that anyone thus outlawed and placed outside the laws and not afterwards restored to his peace, is committed to the forfeiture of his own status or accountability. It is considered that the aforesaid William, for the open sedition which he had made to the same lord the King by felonious contriving, by trying to bring about his death, the destruction and weakening of the crown and of his royal authority and by bringing his standard against his liege lord in war to the death, should be taken away to the palace of Westminster as far as the Tower of London, and from the Tower as far as Allegate [Aldgate], and thus through the middle of the city as far as Elmes, and for the robberies, murders and felonies which he carried out in the kingdom of England and the land of Scotland he should be hanged there and afterwards drawn. And because he had been outlawed and not afterwards restored to the King’s peace, he should be beheaded and decapitated. And afterwards for the measureless wickedness which he did to God and to the most Holy Church by burning churches, vessels and shrines, in which the body of Christ and the bodies of the saints and relics of the same were wont to be placed together, the heart, liver, and lung and all the internal [parts] of the same William, by which such evil thoughts proceeded, should be dispatched to the fire and burned. And also because he had committed both murders and felonies, not only to the lord the King himself but to the entire people of England and Scotland, the body of that William should be cut up and divided and cut up into four quarters, and that the head thus cut off should be affixed upon London bridge in the sight of those crossing both by land and by water, and one quarter should be hung on the gibbet at Newcastle upon Tyne, another quarter at Berwick, a third quarter at Stirling, and a fourth quarter at St John’s town [Perth] as a cause of fear and chastisement of all going past and looking upon these things &c. |

Translated by J. Russell from Documents Illustrative of Sir William Wallace, His Life and Times, ed. Joseph Stevenson, Maitland Club, 1841.

|

SIR WILLIAM WALLACE'S BURIAL PLACE? |

|

We all know the story of Wallace’s betrayal by Monteith at Robroyston, and his subsequent removal to London to be executed for alleged treason in the most barbarous method possible. |

|

|

|

|

WALLACE'S MONUMENTAL BATTLE FOR RECOGNITION |

|

For David Ross it was much more than just another project. It will be the culmination of a pilgrimage to honour a warrior, a hero and an icon of Scottish nationhood. Ross will leave St Albans and complete the last leg of a 500-mile pilgrimage retracing William Wallace's final journey. The 47-year-old hopes to be joined by hundreds of Scots for a march to the spot where 700 years ago one of the nation's greatest national figures and the undisputed leader of the resistance forces was killed. A private commemorative service will then be held inside St Bartholomew the Greater, the oldest church in London. But it will also signal regret for Ross, the convener of the William Wallace Society. Only because of the 700th anniversary of Wallace's death have the public been reminded, albeit temporarily, of the warrior's significance. A historically inaccurate Hollywood film, a few books and a couple of statues in Scottish towns comprise pretty much everything that bears testament to his contribution to the nation. This year, as every year, there is no national holiday or celebration of Wallace's life. What irks Ross, the author of the 1995 book On the Trail of William Wallace, and other Scottish historians is that too few people know the true story of the man who led Scotland to victory over English |

forces at Stirling Bridge in 1297. They have been denied that knowledge through an appalling lack of teaching of Scottish history in our schools and a lack of serious attempts to address our indifference. |

|

|

| Records of Wallace's life are patchy and often inaccurate. Knowledge of him is largely confined to the years of 1297 and 1298. The decision of Randall Wallace to base the script for Braveheart on the late 15th century romance The Wallace, by Blind Harry, ensured a blockbusting tale, vehement in its anti-English tone. Written in 1460 it was the second most popular book in Scotland after the Bible but it did little to aid an accurate historical portrait of Wallace. "Braveheart was a total misrepresentation and a tremendous opportunity lost," said Brown. "The closest it got to accuracy was when Gibson said it was good Scottish weather when rain was falling straight down. The film was complete rubbish." Wallace's life was more complex than a film script allowed. Initially, at least, he led one group of men, not a country. Other men were central to Scotland winning its freedom. Andrew de Moray led battles in northern Scotland, while William Douglas had fought for independence in the Borders. But in a way denied his contemporaries Wallace is feted across the world - if not in his homeland - for his determination to achieve Scottish freedom. At the Tartan Week festivities in New York, in April, more than 250,000 people flocked to see his sword. It is hard to imagine such devotion in Scotland. But who was the real Wallace? According to Brown's book, he was a violent man and the leader of a small band of armoured cavalry who raided isolated parties of English soldiers and officials. But he was not stirred to battle because the English had killed his father, as claimed in Braveheart. "Peace had existed for three generations at that time," Brown said. By 1296 Scotland had been conquered, causing deep resentment. Many of the nobles were imprisoned, they were punitively taxed and expected to serve King Edward I in his military campaigns against France. The flames of revolt spread across Scotland. In May 1297 Wallace slew William Heselrig, the English Sheriff of Lanark. Soon his rising gained momentum, as men "oppressed by the burden of servitude under the intolerable rule of English domination" joined him. From his base in the Ettrick Forest Wallace's followers struck at Scone, Ancrum and Dundee. At the same time in the north, Andrew de Moray led an even more successful rising. From Avoch in the Black Isle, he took Inverness and stormed Urquhart Castle by Loch Ness. His MacDougall allies cleared the west, whilst he struck through the north-east. Wallace's rising drew strength from the south. With most of Scotland liberated, they were prepared for an open battle with an English army. But Wallace was not a great general. He only fought in two battles. He famously won at Stirling Bridge, alongside de Moray, in 1297, when the English were left with 5,000 dead on the field. He became Guardian of Scotland but the position did not last for long. The Battle of Falkirk on July 22 the following year saw Wallace defeated by Edward's army, and he fled underground. |

|

It is thought that the basis of his authority among the people vanished soon after. During his subsequent travels in Europe, Wallace went to France and it is claimed he also met the Pope. But he largely faded away to evade capture, resurfacing in 1304. The following year he was betrayed by Sir John de Menteith while sleeping at a well near Robroyston. Tried for treason at Westminster Hall, Wallace was crowned with a garland of oak to suggest that he was the king of outlaws and declared guilty. On August 23, following the trial, he was removed from the courtroom, stripped naked and dragged to Smithfield Market at the heels of a horse. His terrible fate was surpassed by the grim triumphalism of his enemies' celebrations. Strangled by hanging, but released near death, drawn and quartered and beheaded, Wallace's execution was completed at the Elms in Smithfield, London. His head was placed on a pike atop London Bridge, which was later joined by the heads of his brother, John, and Sir Simon Fraser, who had fought for Robert the Bruce. The English government displayed Wallace's limbs, separately, in Newcastle, Berwick, Stirling and Perth as a warning to others. But it did not manage to strangle the movement that Wallace had started. Instead he provided inspiration for the man who would help Scotland to victory at Bannockburn: Robert The Bruce. The debate rages on whose achievements were greater but more seems to be known about the latter. Brown said: "They will both be remembered as part of the same movement, but if the Bruce had not been successful at the battle of Methven [in 1306] that would have been the end of his attempt to become King." Victory at Bannockburn followed in 1314. But it was not until 1328 that the Treaty of Edinburgh and Northampton ended the wars of Independence. Seven hundred years on, however, academics are united in saying that it was Wallace who started it all and that more should have been done to celebrate the anniversary. Stirling, home to the 220ft high Wallace monument, funded by public subscription and opened in 1869, is one of the few places that has made a concerted attempt to remember Wallace's life. For Ted Cowan, professor of Scottish History at the University of Glasgow, the 700th anniversary of Wallace's execution should be an occasion to celebrate a great life, yet very little has been done. He said: "Wallace was a true national hero: a phenomenon long before Braveheart. There is no other person in Scottish history who really compares to him as a multi-faceted warrior, leader and charismatic figure. After the battle of Stirling Bridge he went to Hamburg to say that Scotland was open for business again. And yet all the Executive has done is organise a dinner at Stirling Castle and a couple of small events." For Ross, the journey has convinced him that Scotland remains paranoid about recognising its greatest historical figures. He said: "When I have spoken to Scottish people about doing this walk in honour of Wallace they often assume that I don't like the English very much. George Washington was responsible for breaking English rule in America but I don't for one minute think people who follow him are seen as anti-English. It is almost a Scottish cringe. An extraordinary knee-jerk reaction." |

CALL FOR RETURN OF WALLACE LETTER |

|

"Phillip (IV), King of France to his lieges at the Roman Court. Commands them to request the Pope's favour for his beloved William le

Wallace of Scotland, Knight, in the matters which he wishes to forward

with His Holiness, Monday after All Saints, Pierrefonds". |

A letter carried by William Wallace in 1305 to grant him safe conduct to visit the pope should be returned to Scotland, according to an MSP. The document has been archived in London since Wallace was tried and executed on charges of treason. Nationalist Jim Mather has lodged a motion at the Scottish Parliament to retrieve it and put it on display. He urged the National Library of Scotland, Scottish Museums and National Archives to join his campaign. The paperwork, written by the King of France, was being carried by Wallace when he was seized in Robroyston near Glasgow. Once here it could be properly displayed and provide a rare tangible link to the national hero The MSP for the Highlands and Islands said the letter, known as The Safe Conduct, should be returned to mark the 700th anniversary of William Wallace's death. "Once here it could be properly displayed and provide a rare tangible link to the national hero, who led the nation at the start of the Wars of Independence," he said. Wallace became a symbol of Scottish nationhood after his victory over the English at the battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297. He was defeated in battle at Falkirk the following year. Wallace was captured in 1305 and was hanged and dismembered with his head put on public display at London Bridge and his limbs sent to Scotland. |

Click HERE to sign the petition |

MENTEITH TRAITOR |

|

Sir John Menteith (c. 1275 - c. 1323) was a Scottish nobleman???? He was born John Stewart in Ruskie, Stirling, Scotland. His father was Walter "Bailloch" Stewart, 5th Earl of Menteith, and mother Mary was the 4th Countess of Menteith. Unlike his older brother, Alexander Stewart, 6th Earl of Menteith, he replaced his paternal Stewart surname in favour of Menteith, which earned him the nickname, Fause (False) Menteith!!!! He was Governor of Dumbarton Castle, an appointment made by Edward I who was keen to secure the fortification as a major access route into Scotland by sea. Tradition has it that Menteith betrayed Sir William Wallace to English soldiers, which led to Wallace's death. |

MENTEITH AND WILLIAM WALLACE |

Much has been written about the nature of Menteith's relationship with Wallace, and his precise role in Wallace's capture. It is unlikely that it will ever be settled beyond doubt. |

1.Sir John Menteith fought on the patriotic side at the Battle of Dunbar in 1296, where he and his older brother were taken prisoner. 2.Menteith made peace with Edward I and pledged support. 3.Menteith returned to the patriotic party. 4.Menteith resubmitted to the English king, and obtained from him the sheriffdom of Dumbarton and the custody of the castle to which Wallace was conveyed after his capture. 5.Menteith obtained a share of the reward that Edward promised to the captors of William Wallace. |

The extent of the friendship between Wallace and Menteith is unknown, but there can be no doubt that they must have had "intercourse and familiarity". In the "Relationes Arnaldi Blair", it is mentioned that in August 1298, Wallace, Governor of Scotland, with John Graham and John Menteith, and Alexander Scrymegour, Constable of Dundee and Standard-bearer of Scotland, fought together in Galloway against the rebels who adhered to the party of Scotland and the Comyns. In the "Chronicle of Lancaster", written in the 13th century, it is stated that "William Wallace was taken by a Scotsman, namely, Sir John Menteith, and carried to London, where he was drawn, hanged, and beheaded." In the account of the capture and execution of Wallace contained in the Arundel manuscript, written about the year 1320, it is stated that "William Wallace was seized in the house of Ralph Rae by Sir John Menteith, and carried to London by Sir John de Segrave, where he was judged." Fordun, who lived in the reign of King Robert I of Scotland (Robert the Bruce), when the memory of the exploits of Wallace must have been quite fresh, says: "The noble William Wallace was, by Sir John Menteith, at Glasgow, while suspecting no evil, fraudulently betrayed and seized, delivered to the King of England, dismembered at London, and his quarters hung up in the towns of the most public places in England and Scotland, in opprobium of the Scots." Wyntoun, whose "Metrical Chronicle" was written in 1418, says: |

"Schyre Jhon of Menteith in tha days Tuk in Glasgow William Walays; And sent hym until Ingland sune, There was he quartayrd and undone." |

The English chronicler Piers Langtoft states that Menteith discovered the retreat of Wallace through the treacherous information of Jack Short, his servant, and that he came under cover of night and seized him in bed. A passage in the Scala Chronica, quoted by Leland, says, "William Walleys was taken of the Counte of Menteith, about Glasgow, and sent to King Edward, and after was hanged, drawn, and quartered at London." But the most conclusive evidence of all that Menteith took a prominent part in the betrayal and capture of Wallace is afforded by the fact that while liberal rewards were given to all the persons concerned in this infamous affair, by far the largest share fell to Menteith: he received land to the value of one hundred pounds. |

We'd like to thank everyone who contributed images to this history lesson, especially artist MURRAY ROBERTSON |

|

© Paisley Tartan Army 2008-09